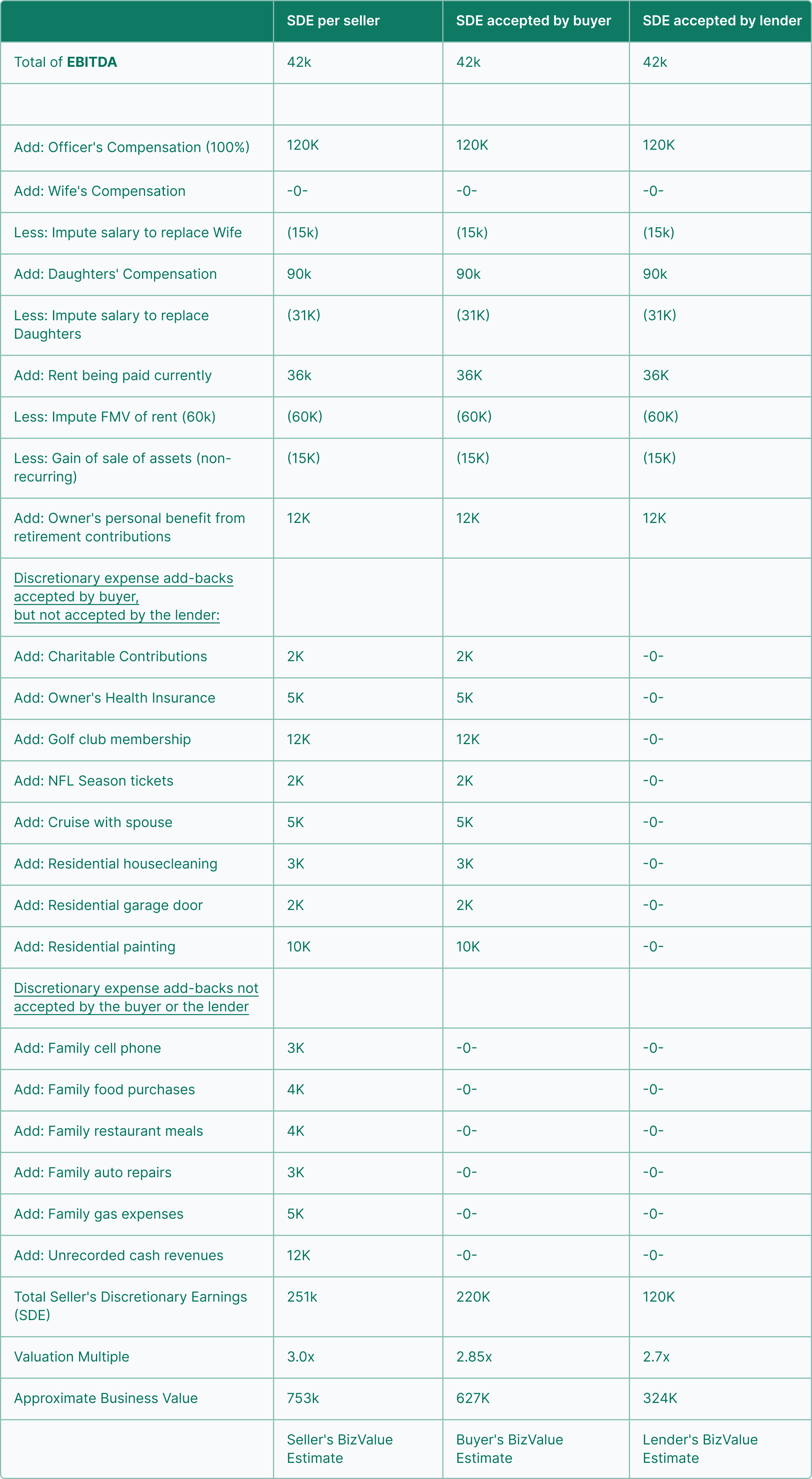

A Seller's Discretionary Earnings (SDE) Worksheet

SDE and Business Valuation Variations amongst Sellers, Buyers and Lenders. In the last issue (#9), we provided an example of A Seller’s Discretionary Earnings (SDE) Worksheet. In this issue we will discuss SDE and Business Valuation Variations amongst Sellers, Buyers and Lenders.

"Credit is a system whereby a person who can not pay gets another person who can not pay to guarantee that he can pay." Charles Dickens

SDE and Business Valuation Variations amongst Sellers, Buyers and Lenders

In the last issue, we provided a detailed 30-item normalization of Seller’s Discretionary Earnings (SDE) for Mr. Husband’s day care center.

In the example below, the seller’s calculation of SDE equaled $251,000, the buyer’s evaluation of SDE totaled $220,000 and the bank’s SDE evaluation totaled only $120,000.

Rather than repeat all the details of the 30 add-back items, below is a consolidated summary of the calculations:

Lenders are very conservative in evaluating discretionary add-backs to SDE

Mr. Husband has a huge problem. He has run so many discretionary and non-business/personal expenses through his business that he has significantly degraded the value of the business. When it comes to discretionary expenses as add-backs to SDE, lenders will not usually accept them. Buyers have the opportunity to perform due diligence, so he might be able to convince them that some discretionary expenses are justified as add-backs to SDE by producing receipts for their review. But lender’s underwriters are not interested in reviewing receipts to approve add-backs for discretionary expenses. It’s just not going to happen. Most lenders limit their SDE calculation to EBITDA plus owner’s salary and few other expenses. They will impute a salary expense to adjust for uncompensated spousal labor and they do want the cost of occupancy (rent) adjusted to fair market value. They may or may not accept the owner benefit from retirement contributions as a valid add-back. But that’s about it. Lenders are notoriously conservative and that definitely holds true in the financing of business acquisitions.

Because of discretionary expenses, the bank values the business at one-half its "true" value

In this example, the bank has valued the business at less than one-half the amount the seller feels his business is worth ($753,000 vs. $324,000). Mr. Husband has overpaid his daughters by $59,000 and has deducted another $72,000 of discretionary and personal expenses on the corporate tax return. His corporation’s tax savings (at an effective corporate rate of 25%) on $131,000 in discretionary expenses is about $33,000. But, that $33,000 in tax savings cost Mr. Husband $429,000 in business valuation (vs. the lender – $753,000 less $324,000)!

This business may not be successfully sold. If it is, Mr. Husband will have to finance a substantial portion of the acquisition price

In light of the circumstances, at what value can Mr. Husband sell his business? Well, that’s difficult to answer. Let’s assume the buyer in this example makes a $627,000 offer that Mr. Husband accepts. When the buyer applies for a loan to finance the acquisition, the lender’s going to conclude the business is worth about $324,000 (because they will not accept the $59,000 in daughters’ excessive salaries as add-backs, nor any of the $72,000 of discretionary expenses). When a lender tells the buyer they can only base a loan on a $324,000 valuation of the business, what’s the buyer going to do? In most instances, with fear of overpaying as a result of the lender’s valuation, the buyer will run the other way! It’s a significant mental obstacle that is very difficult to overcome. Even if Mr. Husband has a buyer who is interested in completing the acquisition, he will probably have to finance more than one-half of the acquisition with a seller’s note.

With adequate planning, Mr. Husband could have sold the business as it "true" value

This example highlights why planning for the sale of your business is so important. Mr. Husband’s day care center really is worth about $750,000, but it is very unlikely to be sold for that amount in its present condition. With three years of advance planning, Mr. Husband could eliminate all $72,000 of discretionary expenses. And, if he took the excessive $59,000 paid to his daughters as additional salary for himself, that $59,000 would be a valid add-back to SDE in the eyes of the lender. With those changes, his profitability would increase by $72,000 and his salary would increase by $59,000. Both the buyer and the lender would evaluate the SDE at the full $251,000 and the business could easily be sold for about $750,000 (assuming all other obstacles have been adequately addressed).

Small businesses are primarily valued based on Seller’s Discretionary Earnings (SDE), but SDE can be subject to interpretation. It’s important to understand that prospective buyers and lenders may not accept all the discretionary expenses and add-backs you might try to include in the calculation of SDE. Although you can negotiate with buyers’ interpretations, there is almost no room to negotiate with lenders’ interpretations and like it or not, lenders are a major factor in the successful sale of a business. However, with adequate planning (preferably three years in advance), this obstacle can be erased by eliminating discretionary expenses being run through your company’s tax return.

When two men in a business always agree, one of them is unnecessary." William Wrigley, Jr.

Overcome the Power of Inertia

Overcome the Power of Inertia and call a business broker for a free consultation. Many brokers offer no-charge, no-obligation evaluations of small businesses. They can provide a broker opinion of value and help you identify obstacles to a successful sale as well as opportunities for improvement to increase the value of your business. That is a great way to start planning for a successful and profitable exit from your business.